Manim’s building blocks#

This document explains the building blocks of manim and will give you all the necessary tools to start producing your own videos.

Essentially, manim puts at your disposal three different concepts that you can

orchestrate together to produce mathematical animations: the

mathematical object (or mobject for short), the animation, and the

scene. As we will see in the following sections, each of these three

concepts is implemented in manim as a separate class: the Mobject,

Animation, and Scene classes.

Note

It is recommended that you read the tutorials Quickstart and Manim’s Output Settings before reading this page.

Mobjects#

Mobjects are the basic building blocks for all manim animations. Each class

that derives from Mobject represents an object that can be displayed

on the screen. For example, simple shapes such as Circle,

Arrow, and Rectangle are all mobjects. More complicated

constructs such as Axes, FunctionGraph, or

BarChart are mobjects as well.

If you try to display an instance of Mobject on the screen, you will only

see an empty frame. The reason is that the Mobject class is an

abstract base class of all other mobjects, i.e. it does not have any

pre-determined visual shape that can be displayed on the screen. It is only the

skeleton of a thing that could be displayed. Therefore, you will rarely need

to use plain instances of Mobject; instead, you will most likely

create instances of its derived classes. One of these derived classes is

VMobject. The V stands for Vectorized Mobject. In essence, a

vmobject is a mobject that uses vector graphics to be displayed. Most of

the time, you will be dealing with vmobjects, though we will continue to use

the term “mobject” to refer to the class of shapes that can be displayed on the

screen, as it is more general.

Note

Any object that can be displayed on the screen is a mobject, even if

it is not necessarily mathematical in nature.

Tip

To see examples of classes derived from Mobject, see the

geometry module. Most of these are in fact derived from

VMobject as well.

Creating and displaying mobjects#

As explained in Quickstart, usually all of the code in a manim

script is put inside the construct() method of a Scene class.

To display a mobject on the screen, call the add() method of the

containing Scene. This is the principal way of displaying a mobject

on the screen when it is not being animated. To remove a mobject from the

screen, simply call the remove() method from the containing

Scene.

Example: CreatingMobjects ¶

from manim import *

class CreatingMobjects(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle()

self.add(circle)

self.wait(1)

self.remove(circle)

self.wait(1)

class CreatingMobjects(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle()

self.add(circle)

self.wait(1)

self.remove(circle)

self.wait(1)

Placing mobjects#

Let’s define a new Scene called Shapes and add()

some mobjects to it. This script generates a static picture that displays a

circle, a square, and a triangle:

Example: Shapes ¶

from manim import *

class Shapes(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle()

square = Square()

triangle = Triangle()

circle.shift(LEFT)

square.shift(UP)

triangle.shift(RIGHT)

self.add(circle, square, triangle)

self.wait(1)

class Shapes(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle()

square = Square()

triangle = Triangle()

circle.shift(LEFT)

square.shift(UP)

triangle.shift(RIGHT)

self.add(circle, square, triangle)

self.wait(1)

By default, mobjects are placed at the center of coordinates, or origin, when

they are first created. They are also given some default colors. Further, the

Shapes scene places the mobjects by using the shift() method. The

square is shifted one unit in the UP direction from the origin, while the

circle and triangle are shifted one unit LEFT and RIGHT, respectively.

Attention

Unlike other graphics software, manim places the center of

coordinates at the center of the screen. The positive vertical

direction is up, and the positive horizontal direction is right.

See also the constants ORIGIN, UP, DOWN, LEFT,

RIGHT, and others, defined in the constants module.

There are many other possible ways to place mobjects on the screen, for example

move_to(), next_to(), and align_to(). The next scene

MobjectPlacement uses all three.

Example: MobjectPlacement ¶

from manim import *

class MobjectPlacement(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle()

square = Square()

triangle = Triangle()

# place the circle two units left from the origin

circle.move_to(LEFT * 2)

# place the square to the left of the circle

square.next_to(circle, LEFT)

# align the left border of the triangle to the left border of the circle

triangle.align_to(circle, LEFT)

self.add(circle, square, triangle)

self.wait(1)

class MobjectPlacement(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle()

square = Square()

triangle = Triangle()

# place the circle two units left from the origin

circle.move_to(LEFT * 2)

# place the square to the left of the circle

square.next_to(circle, LEFT)

# align the left border of the triangle to the left border of the circle

triangle.align_to(circle, LEFT)

self.add(circle, square, triangle)

self.wait(1)

The move_to() method uses absolute units (measured relative to the

ORIGIN), while next_to() uses relative units (measured from the

mobject passed as the first argument). align_to() uses LEFT not as

measuring units but as a way to determine the border to use for alignment. The

coordinates of the borders of a mobject are determined using an imaginary

bounding box around it.

Tip

Many methods in manim can be chained together. For example the two lines

square = Square()

square.shift(LEFT)

can be replaced by

square = Square().shift(LEFT)

Technically, this is possible because most methods calls return the modified mobject.

Styling mobjects#

The following scene changes the default aesthetics of the mobjects.

Example: MobjectStyling ¶

from manim import *

class MobjectStyling(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle().shift(LEFT)

square = Square().shift(UP)

triangle = Triangle().shift(RIGHT)

circle.set_stroke(color=GREEN, width=20)

square.set_fill(YELLOW, opacity=1.0)

triangle.set_fill(PINK, opacity=0.5)

self.add(circle, square, triangle)

self.wait(1)

class MobjectStyling(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle().shift(LEFT)

square = Square().shift(UP)

triangle = Triangle().shift(RIGHT)

circle.set_stroke(color=GREEN, width=20)

square.set_fill(YELLOW, opacity=1.0)

triangle.set_fill(PINK, opacity=0.5)

self.add(circle, square, triangle)

self.wait(1)

This scene uses two of the main functions that change the visual style of a

mobject: set_stroke() and set_fill(). The former changes the

visual style of the mobject’s border while the latter changes the style of the

interior. By default, most mobjects have a fully transparent interior so you

must specify the opacity parameter to display the color. An

opacity of 1.0 means fully opaque, while 0.0 means fully transparent.

Only instances of VMobject implement set_stroke() and

set_fill(). Instances of Mobject implement

set_color() instead. The vast majority of pre-defined classes

are derived from VMobject so it is usually safe to assume that you

have access to set_stroke() and set_fill().

Mobject on-screen order#

The next scene is exactly the same as the MobjectStyling scene from the

previous section, except for exactly one line.

Example: MobjectZOrder ¶

from manim import *

class MobjectZOrder(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle().shift(LEFT)

square = Square().shift(UP)

triangle = Triangle().shift(RIGHT)

circle.set_stroke(color=GREEN, width=20)

square.set_fill(YELLOW, opacity=1.0)

triangle.set_fill(PINK, opacity=0.5)

self.add(triangle, square, circle)

self.wait(1)

class MobjectZOrder(Scene):

def construct(self):

circle = Circle().shift(LEFT)

square = Square().shift(UP)

triangle = Triangle().shift(RIGHT)

circle.set_stroke(color=GREEN, width=20)

square.set_fill(YELLOW, opacity=1.0)

triangle.set_fill(PINK, opacity=0.5)

self.add(triangle, square, circle)

self.wait(1)

The only difference here (besides the scene name) is the order in which the

mobjects are added to the scene. In MobjectStyling, we added them as

add(circle, square, triangle), whereas in MobjectZOrder we add them as

add(triangle, square, circle).

As you can see, the order of the arguments of add() determines

the order that the mobjects are displayed on the screen, with the left-most

arguments being put in the back.

Animations#

At the heart of manim is animation. Generally, you can add an animation to

your scene by calling the play() method.

Example: SomeAnimations ¶

from manim import *

class SomeAnimations(Scene):

def construct(self):

square = Square()

# some animations display mobjects, ...

self.play(FadeIn(square))

# ... some move or rotate mobjects around...

self.play(Rotate(square, PI/4))

# some animations remove mobjects from the screen

self.play(FadeOut(square))

self.wait(1)

class SomeAnimations(Scene):

def construct(self):

square = Square()

# some animations display mobjects, ...

self.play(FadeIn(square))

# ... some move or rotate mobjects around...

self.play(Rotate(square, PI/4))

# some animations remove mobjects from the screen

self.play(FadeOut(square))

self.wait(1)

Put simply, animations are procedures that interpolate between two mobjects.

For example, FadeIn(square) starts with a fully transparent version of

square and ends with a fully opaque version, interpolating between them

by gradually increasing the opacity. FadeOut works in the opposite

way: it interpolates from fully opaque to fully transparent. As another

example, Rotate starts with the mobject passed to it as argument, and

ends with the same object but rotated by a certain amount, this time

interpolating the mobject’s angle instead of its opacity.

Animating methods#

Any property of a mobject that can be changed can be animated. In fact, any

method that changes a mobject’s property can be used as an animation, through

the use of animate().

Example: AnimateExample ¶

from manim import *

class AnimateExample(Scene):

def construct(self):

square = Square().set_fill(RED, opacity=1.0)

self.add(square)

# animate the change of color

self.play(square.animate.set_fill(WHITE))

self.wait(1)

# animate the change of position and the rotation at the same time

self.play(square.animate.shift(UP).rotate(PI / 3))

self.wait(1)

class AnimateExample(Scene):

def construct(self):

square = Square().set_fill(RED, opacity=1.0)

self.add(square)

# animate the change of color

self.play(square.animate.set_fill(WHITE))

self.wait(1)

# animate the change of position and the rotation at the same time

self.play(square.animate.shift(UP).rotate(PI / 3))

self.wait(1)

References: Animation

animate() is a property of all mobjects that animates the methods that come

afterward. For example, square.set_fill(WHITE) sets the fill color of

the square, while square.animate.set_fill(WHITE) animates this action.

Animation run time#

By default, any animation passed to play() lasts for exactly one second.

Use the run_time argument to control the duration.

Example: RunTime ¶

from manim import *

class RunTime(Scene):

def construct(self):

square = Square()

self.add(square)

self.play(square.animate.shift(UP), run_time=3)

self.wait(1)

class RunTime(Scene):

def construct(self):

square = Square()

self.add(square)

self.play(square.animate.shift(UP), run_time=3)

self.wait(1)

Creating a custom animation#

Even though Manim has many built-in animations, you will find times when you need to smoothly animate from one state of a Mobject to another.

If you find yourself in that situation, then you can define your own custom animation.

You start by extending the Animation class and overriding its interpolate_mobject().

The interpolate_mobject() method receives alpha as a parameter that starts at 0 and changes throughout the animation.

So, you just have to manipulate self.mobject inside Animation according to the alpha value in its interpolate_mobject method.

Then you get all the benefits of Animation such as playing it for different run times or using different rate functions.

Let’s say you start with a number and want to create a Transform animation that transforms it to a target number.

You can do it using FadeTransform, which will fade out the starting number and fade in the target number.

But when we think about transforming a number from one to another, an intuitive way of doing it is by incrementing or decrementing it smoothly.

Manim has a feature that allows you to customize this behavior by defining your own custom animation.

You can start by creating your own Count class that extends Animation.

The class can have a constructor with three arguments, a DecimalNumber Mobject, start, and end.

The constructor will pass the DecimalNumber Mobject to the super constructor (in this case, the Animation constructor) and will set start and end.

The only thing that you need to do is to define how you want it to look at every step of the animation.

Manim provides you with the alpha value in the interpolate_mobject() method based on frame rate of video, rate function, and run time of animation played.

The alpha parameter holds a value between 0 and 1 representing the step of the currently playing animation.

For example, 0 means the beginning of the animation, 0.5 means halfway through the animation, and 1 means the end of the animation.

In the case of the Count animation, you just have to figure out a way to determine the number to display at the given alpha value and then set that value in the interpolate_mobject() method of the Count animation.

Suppose you are starting at 50 and incrementing until the DecimalNumber reaches 100 at the end of the animation.

If alpha is 0, you want the value to be 50.

If alpha is 0.5, you want the value to be 75.

If alpha is 1, you want the value to be 100.

Generally, you start with the starting number and add only some part of the value to be increment according to the alpha value.

So, the logic of calculating the number to display at each step will be 50 + alpha * (100 - 50).

Once you set the calculated value for the DecimalNumber, you are done.

Once you have defined your Count animation, you can play it in your Scene for any duration you want for any DecimalNumber with any rate function.

Example: CountingScene ¶

from manim import *

class Count(Animation):

def __init__(self, number: DecimalNumber, start: float, end: float, **kwargs) -> None:

# Pass number as the mobject of the animation

super().__init__(number, **kwargs)

# Set start and end

self.start = start

self.end = end

def interpolate_mobject(self, alpha: float) -> None:

# Set value of DecimalNumber according to alpha

value = self.start + (alpha * (self.end - self.start))

self.mobject.set_value(value)

class CountingScene(Scene):

def construct(self):

# Create Decimal Number and add it to scene

number = DecimalNumber().set_color(WHITE).scale(5)

# Add an updater to keep the DecimalNumber centered as its value changes

number.add_updater(lambda number: number.move_to(ORIGIN))

self.add(number)

self.wait()

# Play the Count Animation to count from 0 to 100 in 4 seconds

self.play(Count(number, 0, 100), run_time=4, rate_func=linear)

self.wait()

class Count(Animation):

def __init__(self, number: DecimalNumber, start: float, end: float, **kwargs) -> None:

# Pass number as the mobject of the animation

super().__init__(number, **kwargs)

# Set start and end

self.start = start

self.end = end

def interpolate_mobject(self, alpha: float) -> None:

# Set value of DecimalNumber according to alpha

value = self.start + (alpha * (self.end - self.start))

self.mobject.set_value(value)

class CountingScene(Scene):

def construct(self):

# Create Decimal Number and add it to scene

number = DecimalNumber().set_color(WHITE).scale(5)

# Add an updater to keep the DecimalNumber centered as its value changes

number.add_updater(lambda number: number.move_to(ORIGIN))

self.add(number)

self.wait()

# Play the Count Animation to count from 0 to 100 in 4 seconds

self.play(Count(number, 0, 100), run_time=4, rate_func=linear)

self.wait()

References: Animation DecimalNumber interpolate_mobject() play()

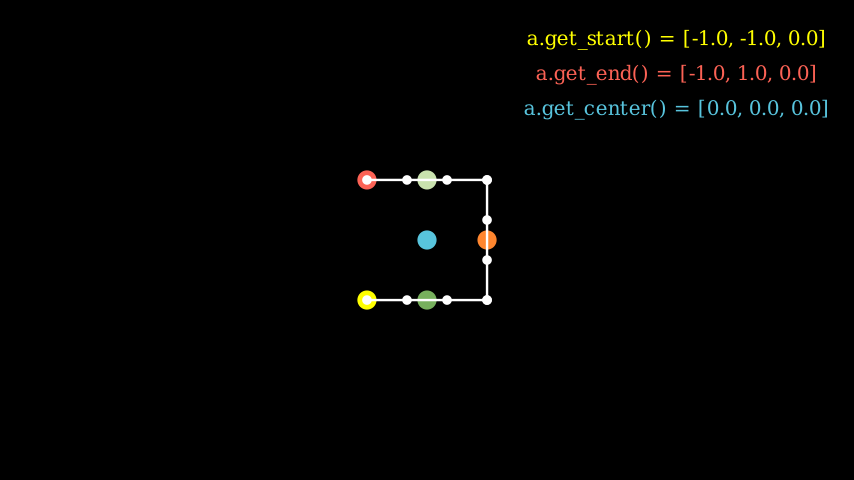

Using coordinates of a mobject#

Mobjects contain points that define their boundaries.

These points can be used to add other mobjects respectively to each other,

e.g. by methods like get_center() , get_top()

and get_start(). Here is an example of some important coordinates:

Example: MobjectExample ¶

from manim import *

class MobjectExample(Scene):

def construct(self):

p1= [-1,-1,0]

p2= [1,-1,0]

p3= [1,1,0]

p4= [-1,1,0]

a = Line(p1,p2).append_points(Line(p2,p3).points).append_points(Line(p3,p4).points)

point_start= a.get_start()

point_end = a.get_end()

point_center = a.get_center()

self.add(Text(f"a.get_start() = {np.round(point_start,2).tolist()}", font_size=24).to_edge(UR).set_color(YELLOW))

self.add(Text(f"a.get_end() = {np.round(point_end,2).tolist()}", font_size=24).next_to(self.mobjects[-1],DOWN).set_color(RED))

self.add(Text(f"a.get_center() = {np.round(point_center,2).tolist()}", font_size=24).next_to(self.mobjects[-1],DOWN).set_color(BLUE))

self.add(Dot(a.get_start()).set_color(YELLOW).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_end()).set_color(RED).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_top()).set_color(GREEN_A).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_bottom()).set_color(GREEN_D).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_center()).set_color(BLUE).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.point_from_proportion(0.5)).set_color(ORANGE).scale(2))

self.add(*[Dot(x) for x in a.points])

self.add(a)

class MobjectExample(Scene):

def construct(self):

p1= [-1,-1,0]

p2= [1,-1,0]

p3= [1,1,0]

p4= [-1,1,0]

a = Line(p1,p2).append_points(Line(p2,p3).points).append_points(Line(p3,p4).points)

point_start= a.get_start()

point_end = a.get_end()

point_center = a.get_center()

self.add(Text(f"a.get_start() = {np.round(point_start,2).tolist()}", font_size=24).to_edge(UR).set_color(YELLOW))

self.add(Text(f"a.get_end() = {np.round(point_end,2).tolist()}", font_size=24).next_to(self.mobjects[-1],DOWN).set_color(RED))

self.add(Text(f"a.get_center() = {np.round(point_center,2).tolist()}", font_size=24).next_to(self.mobjects[-1],DOWN).set_color(BLUE))

self.add(Dot(a.get_start()).set_color(YELLOW).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_end()).set_color(RED).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_top()).set_color(GREEN_A).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_bottom()).set_color(GREEN_D).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.get_center()).set_color(BLUE).scale(2))

self.add(Dot(a.point_from_proportion(0.5)).set_color(ORANGE).scale(2))

self.add(*[Dot(x) for x in a.points])

self.add(a)

Transforming mobjects into other mobjects#

It is also possible to transform a mobject into another mobject like this:

Example: ExampleTransform ¶

from manim import *

class ExampleTransform(Scene):

def construct(self):

self.camera.background_color = WHITE

m1 = Square().set_color(RED)

m2 = Rectangle().set_color(RED).rotate(0.2)

self.play(Transform(m1,m2))

class ExampleTransform(Scene):

def construct(self):

self.camera.background_color = WHITE

m1 = Square().set_color(RED)

m2 = Rectangle().set_color(RED).rotate(0.2)

self.play(Transform(m1,m2))

The Transform function maps points of the previous mobject to the points of the next mobject. This might result in strange behaviour, e.g. when the dots of one mobject are arranged clockwise and the other points are arranged counterclockwise. Here it might help to use the flip function and reposition the points via the roll function of numpy:

Example: ExampleRotation ¶

from manim import *

class ExampleRotation(Scene):

def construct(self):

self.camera.background_color = WHITE

m1a = Square().set_color(RED).shift(LEFT)

m1b = Circle().set_color(RED).shift(LEFT)

m2a= Square().set_color(BLUE).shift(RIGHT)

m2b= Circle().set_color(BLUE).shift(RIGHT)

points = m2a.points

points = np.roll(points, int(len(points)/4), axis=0)

m2a.points = points

self.play(Transform(m1a,m1b),Transform(m2a,m2b), run_time=1)

class ExampleRotation(Scene):

def construct(self):

self.camera.background_color = WHITE

m1a = Square().set_color(RED).shift(LEFT)

m1b = Circle().set_color(RED).shift(LEFT)

m2a= Square().set_color(BLUE).shift(RIGHT)

m2b= Circle().set_color(BLUE).shift(RIGHT)

points = m2a.points

points = np.roll(points, int(len(points)/4), axis=0)

m2a.points = points

self.play(Transform(m1a,m1b),Transform(m2a,m2b), run_time=1)

Scenes#

The Scene class is the connective tissue of manim. Every mobject has

to be added to a scene to be displayed, or removed from it to cease being displayed. Every animation has to be

played by a scene, and every time interval where no

animation occurs is determined by a call to wait(). All of the

code of your video must be contained in the construct() method of

a class that derives from Scene. Finally, a single file may contain

multiple Scene subclasses if multiple scenes are to be

rendered at the same time.